Why our financial literacy matters.

While knowledge is power, the lack of knowledge can leave us vulnerable in many areas of life.

This is especially true when it comes to our relationship with money.

Financial literacy is the missing building block undermining many people’s financial capability and personal financial position, invariably leading to chronic financial stress issues.

According to the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center, the research found that financial stress and anxiety are highly linked to low levels of financial literacy, problematic financial behaviours and decreased financial security.

The situation has worsened during the pandemic.

It is also widely accepted women have lower levels of financial literacy than men, including in Australia which is in the top 10 nations for financial literacy.

In Australia, 63% of men and 48% of women demonstrate an understanding of at least three basic financial literacy concepts, according to data collected in the national Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey.

Questions asked of respondents in the HILDA survey were:

Q1: Interest Rate

“Suppose you put $100 into a no-fee savings account with a guaranteed interest rate of 2% per year. You don’t make any further payments into this account and you don’t withdraw any money. How much would be in the account at the end of the first year, once the interest payment is made?”

Q2: Inflation

“Imagine now that the interest rate on your savings account was 1% per year and inflation was 2% per year. After one year, would you be able to buy more than today, the same as today, or less than today with the money in this account?”

Q3: Diversification

“Buying shares in a single company usually provides a safer return than buying shares in a number of different companies.” [True or False]

Q4: Risk

“An investment with a high return is likely to be high risk.” [True, False]

Q5: Money Illusion

“Suppose that by the year 2020 your income has doubled, but the prices of all of the things you buy have also doubled. In 2020, will you be able to buy more than today, exactly the same as today, or less than today with your income?”

If understanding three basic financial literacy concepts can be considered financially literate, then these statistics suggest that around 8.5 million (or 45%) adults in Australia are financially illiterate

But few of us want to talk about the reality of financial capability – or our financial incapability, as the case may be.

Sadly, there is considerable shame associated with saying ‘I don’t understand how my Afterpay works, or my credit card statements, let alone how to effectively manage something as complex as share trading, as detailed as the fine print in a product disclosure statement or as expensive as a 30-year mortgage.

Many of us don’t even truly understand how our phone plans work, or what everything on our payslips means.

According to findings from the United States’ National Financial Capability Study, just 34% of Americans can answer four or five questions on a basic five-question financial literacy quiz correctly.

‘Study participants were asked five questions covering aspects of economics and finance encountered in everyday life, such as compound interest, inflation, principles relating to risk and diversification, the relationship between bond prices and interest rates, and the impact that a shorter-term can have on total interest payments over the life of a mortgage.’

‘Individuals need at least a fundamental level of financial knowledge. This knowledge, paired with financial decision-making skills, can best ensure an individual’s financial capability.’

It’s human nature to want to ‘set and forget’ complex financial issues, and too much product and service marketing leave us with the comforting but untrue idea that we can do that.

Financial instruments, personal situations all change – so our actions around finances must change too. Big companies are nimble and unless we want to pay too much, we need to at least understand that our personal financial decisions need to be flexible and we must be prepared to embrace changes in our finances.

But how do we know where to start?

But as the saying goes, we don’t know what we don’t know.

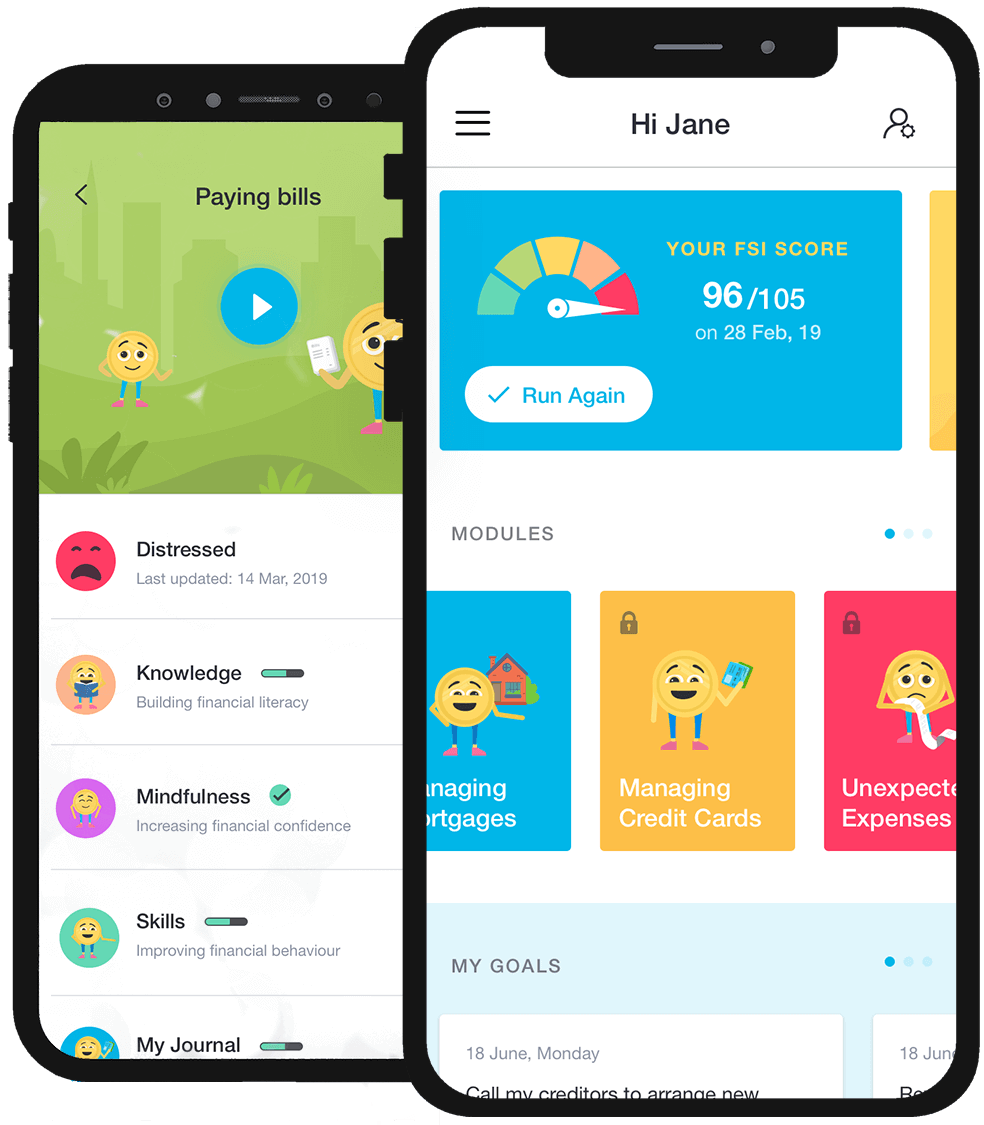

Financial mindfulness is a state of awareness and attention to your finances and financial behaviours that can support the growth of your financial literacy.

It is not the answer to a lack of financial literacy, but it can help us see reality and feel motivated to learn.

A key part of mindfulness is to observe our thoughts, feelings and behaviours as they are – not how we think they should be. This allows us to see the world as it is, rather than just accepting autopilot as a life-long strategy.

In the context of personal finances, developing financial mindfulness is a clear and useful step towards improving financial literacy.

In the second part of this two-part series, we will look at a range of clear steps to improve your financial literacy.

Next week: Ten steps to increase your financial literacy.