Managing financial stress and mindfulness.

In the second part of our financial stress webinar covering managing financial stress, we look at goals, mindfulness, and monitoring progress with expert help from Lea Clothier, a Master-certified behavioural money coach involved in the development of the Financial Mindfulness program. Part one looked in detail, decision making, literacy, and learning new skills.

Setting financial goals

By definition, moving forward – out of financial stress – means we have to do things differently.

“If we stay where we are, we’re going to get more of what we’ve got,” Ms. Clothier says.

The reason for setting financial goals is because they can help unlock genuine and transformative behaviour change.

The theory of behaviour change is that we need to be motivated to make changes. Setting goals is a way of taking early but clear steps towards change.

“These goals can be tiny, or they can be very significant. I’m a big fan of what they call small but significant goals,” says Ms. Clothier.

One type of goal is a milestone – reaching a certain target of savings or being able to afford something we’ve targeted, like the deposit to buy a property, or fund a small business.

On top of the achievement of reaching a goal, the very act of setting financial goals can actually help reduce financial stress because it makes us feel a little more positive about our money.

“We can start to see the progress that we’re taking away from what we don’t want, towards that which we do want,” Ms. Clothier says.

In setting financial goals it’s a good idea to nominate an ‘accountability partner’ and make them part of your process.

That is a person to check in with around your progress.

The more you think about how you got into financial stress – this point where major change is necessary – and reflect on your history of self-defeating or disorganised behaviours with money, the more you’ll see accountability is essential in changing your relationship with financial stress.

It’s important to note things may not happen quickly. Making a meaningful change that can be sustained for a lifetime will probably be slow.

It is also just a reality that we are likely to go through periods of not seeing any changes or slipping back into old patterns with money.

That might seem depressing, but depending on your perspective and openness to change, the re-emergence of old habits is an opportunity.

How?

We have a clear choice: we can slip backward and give up or re-evaluate our goal, our process and perhaps set a new smaller financial goal.

Small financial goals and milestones are also rewarding.

It’s well-known by experts in goal-setting that most goals consist of smaller tangible goals, like stepping stones on a path.

“I’m also a fan of doing something physical to acknowledge reaching goals,” says Ms. Clothier.

“Whether that be like marking off a calendar every time you complete payment towards debt or colouring in a picture that has 52 elements of savings that you’re doing weekly over a year.”

This is important and useful because our relationship with money has become even more abstract than it was: very often we don’t even see or touch money in our cashless society.

Because so many transactions have become contactless or online during the pandemic the likelihood of not carrying any cash at all has increased for millions of us.

“We have lost that connection to the reality of our physical relationship with money,” she says.

“That money ‘disconnect’ is very real and it helps our ability to reach financial goals if we can get back a sense of connection to money.”

We are more likely to think of concepts and issues every day if we feel connected to them.

Discovering the power of mindfulness

Lea Clothier trained as a meditation and yoga teacher when she saw clients to her money behavioural coaching business were suffering acute stress.

“When they started to talk about money, they talked about their hopes and dreams with cash or their actual reality with money I could see that it was stressful, and I could see that stress was directly linked to their wellbeing,” she says.

Financial stress is a type of stress, and as we discussed in a previous blog which means it responds to a range of stress reduction techniques, including mindfulness.

Mindfulness – which at its most basic is about bringing our awareness to the present moment – is an important stress reduction technique.

“It means we are paying attention; we’re fully invested in this very moment,” Ms. Clothier says.

“We do that through the application of our five senses. It means that we start to pay more attention to our touch, our sight, what we can smell, hear and taste.”

“By doing that, we get out of that hectic, noisy head of thoughts that all of us have.”

The power of mindfulness with money is it’s two-fold.

It means we need to bring our full attention to our finances.

We need to pay attention to what’s going on in our bank accounts, with our spending, in how we earn money, and in the way that we interact with money every time we use it.

Mindfulness also has the power to help to reduce our stress levels. It is known and proven to be able to reduce cortisol, the stress hormone.

There is also research to show mindfulness can actually increase the density of the pre-frontal cortex, also known as ‘the thinking brain’.

This is important because our responses to money are so often based on how we feel and our emotions.

This means that we’re reacting when we’re interacting with money; we’re not responding. We’re not making logical, clear, calm, well-thought-out decisions.

“For me, mindfulness is like a superpower when it comes to our finances,” Ms. Clothier says.

“It’s a way to slow down and give provide enough space to practice better decisions and practice a better way to manage money.

“Think about when you’re in the shopping centre, and you’re about to buy something. You’re not thinking much about it, you just like it, you’ve seen it and you want it.”

“You go to the counter, you tap as you go, you walk out, and as you leave, you get in the car, you go home. You get home, and you go, “Argh, I probably shouldn’t have bought that. I don’t have the money, and I’ve got those bills coming up.”

The emotional part of the brain reacts seven seconds faster than the thinking part. It’s unlikely we would turn to the knowledge gained in improving our financial literacy in that time.

But we can just stop.

A mindful approach with money in that situation would involve, slowing down our actions, and stopping before tapping the card, taking a breath, and checking in about how important the item really is?

The same can apply to investing in the share market, or lending money to family or friends for them to invest.

But by approaching and adopting mindfulness, we just slow everything down, and we don’t react.

“We can stop and consider the repercussions of any decision or action before making it.”

How to measure and monitor our progress

Very few of us know how financially stressed we really are. We need to have some kind of idea of this before we really know what progress looks like.

To measure financial stress, we need to look at more than just our bank account balances.

The context for how we spend, why we spend, and what we spend it on matters a great deal.

“Think to the gym and doing a fitness assessment before you get there,” Ms. Clothier says.

“Where you’re sitting with your PT, and they’re saying okay, ‘tell me about your diet, tell me about your state of mind, your sleep patterns, tell me about your exercise routines.”

“It’s the same concept as that, except it applies to your relationship with money instead of food or exercise.”

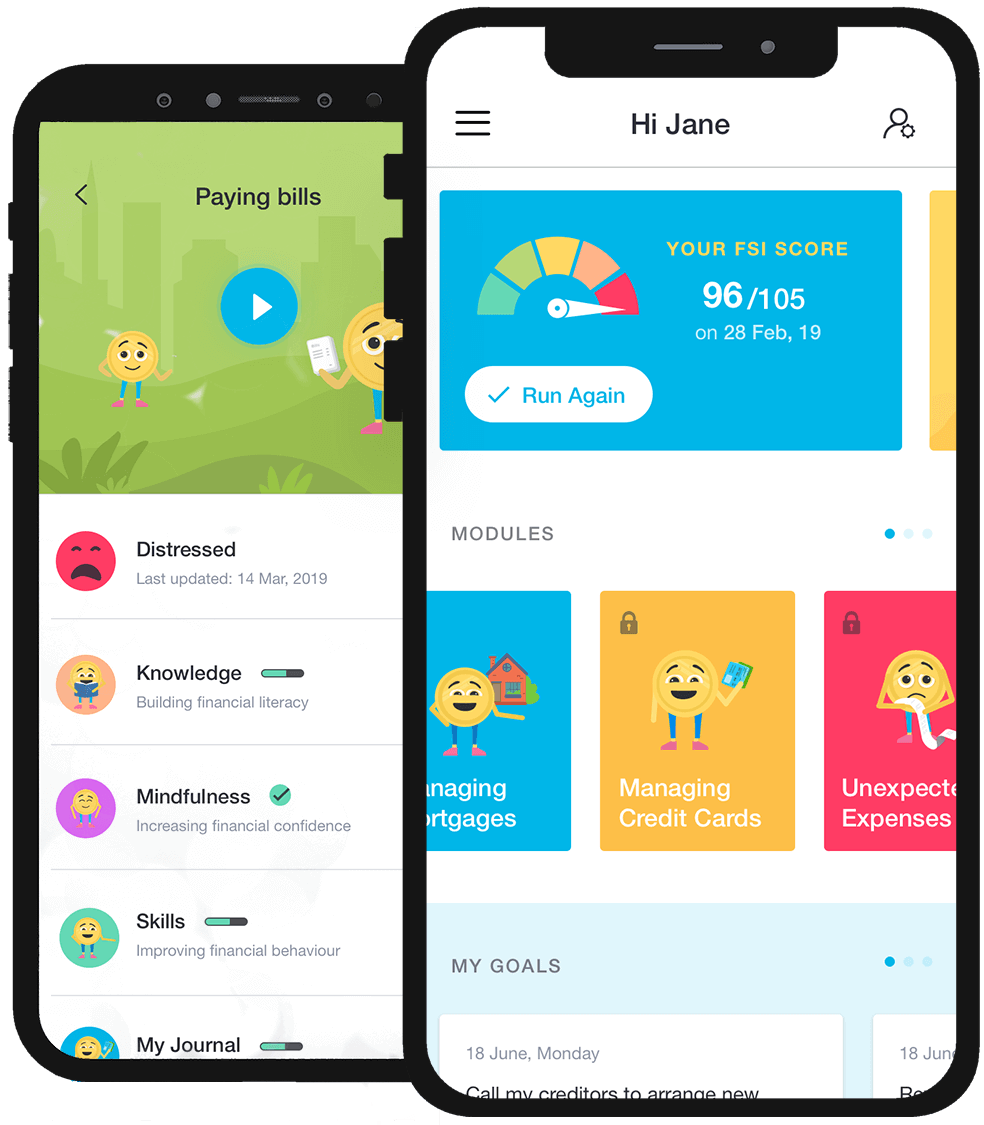

Financial Mindfulness developed the Financial Stress Index (FSI) as a way to measure and monitor the financial stress of individuals and groups of people in detail.

It is contained within the Financial Mindfulness app and measures the levels of financial stress on five dimensions with suggested solutions for individuals.

These are the financial status, the physical and psychological burden, the social engagement, the psychological impact, and the behavioural signs of stress.

The score given to each user is a starting point, a baseline.

Returning to doing the FSI every 30 days or more allows users to clearly see their progress across the five dimensions.