[email-subscribers-form id=”2″]

Mindfulness and the Sunk Cost Bias

Understanding the Sunk-Cost Fallacy

If you’ve ever persisted with a dead-end job, loveless relationship, or regrettable university degree, hoping it will somehow improve, or ‘chased your losses’ by doubling down, this article is for you, Mindfulness and the Sunk Cost Bias.

Maybe you’ve endured reading a novel you hated after the first three chapters or stayed through a movie just because you bought tickets, despite wanting to leave.

Have you ever done something similar with money?

Plunged money into a stock, a small business, or tried your hand at foreign currency trading without understanding it?

Hung onto a car for too long even when it’s cost you a fortune?

All these actions, where we ‘throw good money after bad’, are examples of the sunk-cost fallacy, an economic principle that can be applied to life in general.

What is the Sunk-Cost Fallacy

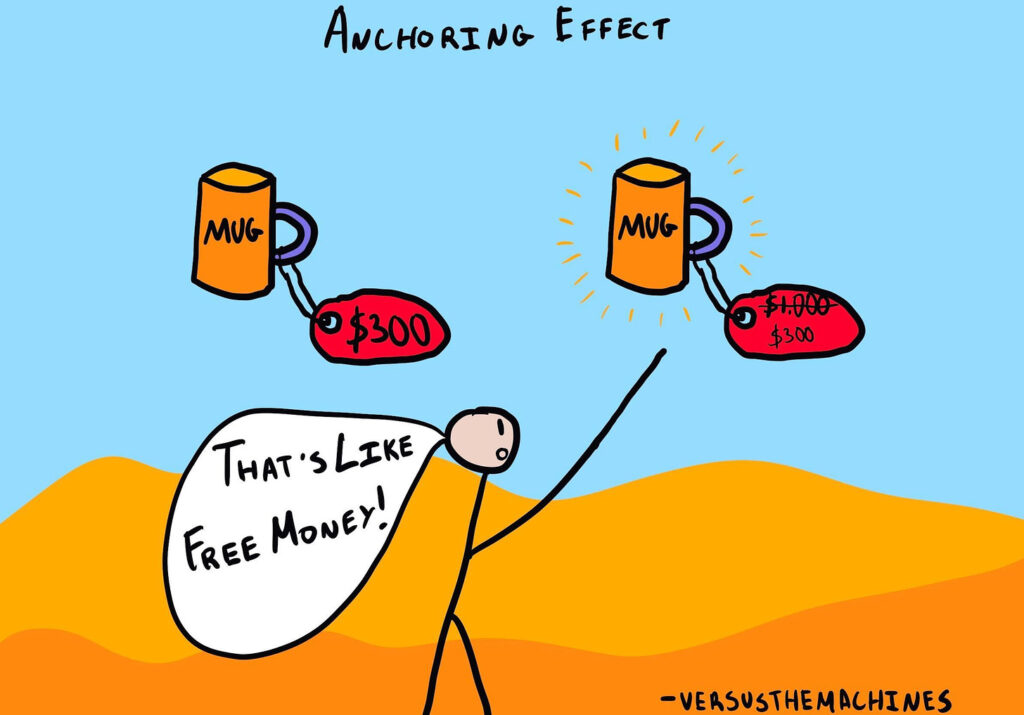

The sunk-cost fallacy is the tendency to continue with an irrational and often risky course of action, not based on the likely outcome, but because we don’t want to ‘waste’ what are unrecoverable costs and time – also known as ‘sunk costs’.

It’s a very human response to try even harder to win after a loss, sometimes to avoid feelings of guilt or inadequacy, or even just fear of ‘looking bad’.

However, ego, politics, and emotional decision-making can cause people to double or triple their financial losses, resulting in huge financial and emotional stress for individuals and their families.

Recognizing Irrational Decisions

In the cold light of day, it’s not rational to continue investing in a failing venture, but who hasn’t done something like this? More importantly, how do we stop this apparent madness?

Mindfulness and the Sunk-Cost Bias

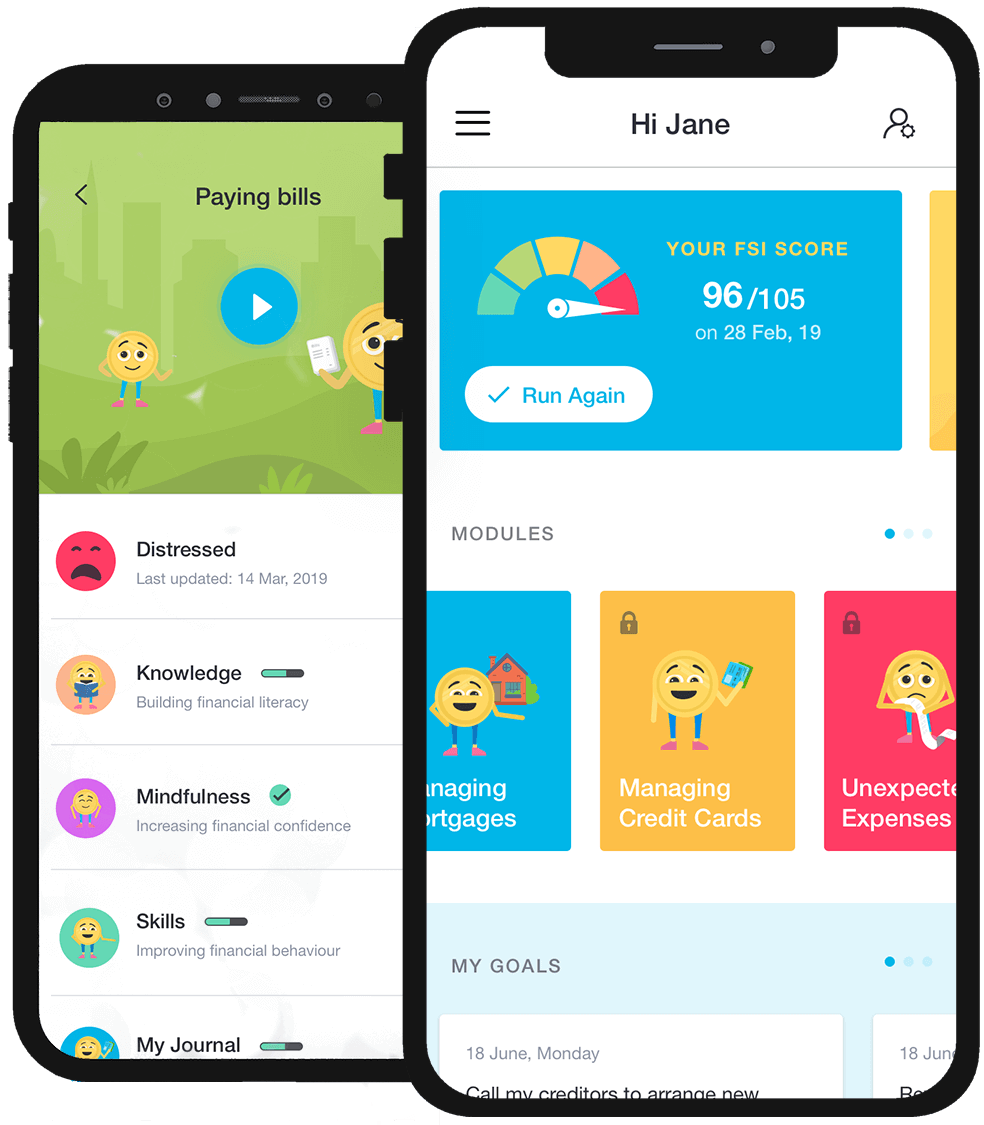

Researchers Andrew Hafenbrack, Zoe Kinias, and Sigal Barsade published their work, “Debiasing the Mind Through Meditation: Mindfulness and the Sunk-Cost Bias,” in the Journal of Psychological Science in 2013.

Their research suggests that increased mindfulness reduces the tendency to allow unrecoverable prior costs to influence current decisions.

“Meditation reduced how much people focused on the past and future, and this psychological shift led to less negative emotion,” Kinias wrote in the journal. “The reduced negative emotion facilitated their ability to let go of sunk costs.” Mindfulness does have some power over bad financial decision-making!

Mindfulness and Gambling Outcomes

In another study, from Elsevier’s journal Personality and Individual Differences in 2007, researchers Chad Lakey, Keith Campbell, Adam Goodie (University of Georgia), and Kirk Warren Brown (Virginia Commonwealth University) found that “mindfulness is associated with less severe gambling outcomes.”

They concluded, “The greater attention to and awareness of ongoing internal and external stimuli that characterizes mindfulness may represent an effective means of mitigating the impulsive and addictive responses and intemperate risk-attitudes of individuals with problem gambling.”

Practical Steps to Mitigate Financial Stress

Practice Mindfulness

Incorporate regular mindfulness practices to reduce emotional responses and improve decision-making.

Evaluate Decisions Logically

Separate emotions from financial decisions. Assess the situation based on current facts, not past investments.

Set Clear Financial Goals

Establish clear, rational financial goals and stick to them.

Seek Professional Advice

Consult financial advisors or behavioral coaches to guide you in making informed decisions.

Monitor Progress

Regularly review your financial decisions and adjust strategies as needed.

Conclusion

Research into the specific benefits of mindfulness is ongoing, but it is clear that a regular mindfulness practice can have powerful positive effects on dysfunctional decision-making around money.

By understanding the sunk-cost fallacy and incorporating mindfulness, you can make better financial decisions and reduce the emotional and financial stress caused by past mistakes.