[email-subscribers-form id=”2″]

Avoid impulse spending – Black Friday and Cyber Monday sales

Avoid impulse spending – Black Friday and Cyber Monday sales.

Black Friday and Cyber Monday sales are upon us, with a marketing onslaught that can be hard to resist.

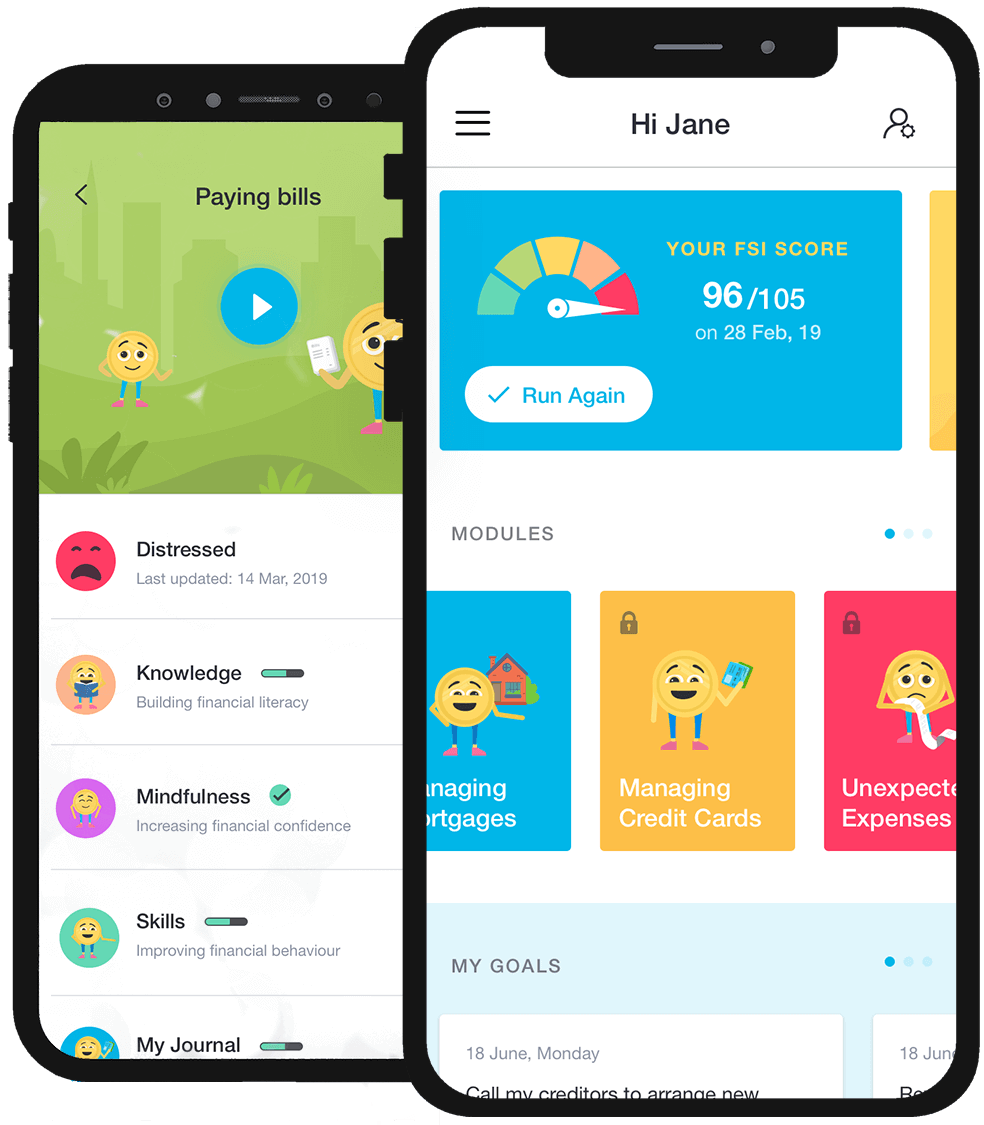

The ideal mindset, when faced with the temptation to spend, is to be financially mindful – fully aware of your financial position and real needs.

The word ‘frenzy’ is not the optimal environment to maintain financial mindfulness and avoid financial stress. But a shopping frenzy is exactly what is expected, beginning next week.

‘Australian retailers can look forward to a sales frenzy over the Black Friday and Cyber Monday shopping period, with a record $6.2 billion predicted to be spent in stores and online according to research from the Australian Retailers Association’, research firm Roy Morgan reported.

The four-day shopping period from November 25 (when Black Friday sales begin) to November 28 (Cyber Monday) began in the United States and has gone from strength to strength in Australia.

The 4 days shopping period has extended even further, making the actual period 11 days! As I write this article, my email inbox has already been inundated with Black Friday specials. Email titles such as;

“VIP Black Friday starts now – GO!”

“LIFT OFF, EARLY BIRD”

“Black Friday has arrived EARLY FOR YOU”

In the US, Black Friday is always the day after Thanksgiving. While it’s not an official holiday, many people have the day off (except those who work in retail).

This year, Future Publishing predicts that Black Friday will raise USD$158 billion in total sales.

The marketing for ‘hot deals’, designed to draw in shoppers, has already began, with Amazon among companies already seeking to entice spending.

Consumer spending is good for the economy, but with a frenzy about to hit, ‘strength’ is being replaced by ‘mania’.

Frenzied behaviour when shopping, especially when the payment methods are the deferred – such as buy now, pay later accounts or the ever-popular credit card – can mean sustained impulse spending.

Impulse spending is a recipe for financial stress, especially when bills begin to fall due.

Let’s drill down to the specifics of why we should pull ourselves – and our households – back to a mindset of mindful spending next week – and keep that mindset right through Christmas and beyond January sales.

The first thing to get real about is whether you already have disorganised finances. If you – or your household – does, then a period of sustained impulse spending is likely to cause problems.

What is impulse spending?

Impulse spending is when you purchase something that you weren’t planning to.

It is your unplanned spending, or when you purchase something without considering the consequences of the purchase and are acting on ‘impulse’, i.e. a sudden strong and unreflective urge or desire to act.

At this time of year, that could range from extra Christmas decorations to hotel deals to the latest smartphone or putting a deposit on a brand-new car.

Everyone behaves impulsively at times, and it’s not always bad. It can be fun and harmless, so long as it’s measured and your finances are in order.

But we need to be clear. Regular impulse and unplanned spending can ruin your budget, create a debt spiral and impact on your ability to achieve your financial goals.

If your goal is getting out of debt, then impulsive spending is damaging.

The same goes for goals like paying off your mortgage, saving for a holiday or investing for your future.

Buying on impulse and overspending will use up money you could otherwise put toward your goals.

Let’s look at spending via social media, which has been growing in recent years.

According to a study by Finder, the average Australian spends $860 per annum on purchases made through social media, that’s $71.66 per month.

Investing $71.66 for 10 years at 8 per cent pa would grow nearly $13,000 over 10 years.

That type of equation is known as ‘opportunity cost’ – the cost of one item is the lost opportunity to do or consume something else.

Impulse spending is one of the main underlying money habits that create financial stress – which we know from research creates feelings of shame, guilt, confusion, anxiety, fear – and relationship issues.

If we cannot deal with these feelings and an emerging issue in our finances, some people turn to dysfunctional strategies like using short-term loans or even gambling to try and solve their problems. Or they may begin to drink more alcohol or return to smoking cigarettes to cope.

What drives impulse spending

Your emotions play a huge part in what you buy and how you buy.

Impulse spending occurs when we make spending decisions based on pure emotion.

Knowing your personal motivations and main triggers to impulse spending will help you to manage your money and impulse spending habits better.

Your personal finances are just that: personal, so it makes sense that when something’s going on in your personal life, it is likely to show up in your spending habits too.

Triggers that can lead to impulsive shopping include:

-

- Excitement, including ‘bargain’ revelations;

- Avoiding reality;

- Stressed, overwhelmed;

- Bored, distracted;

- Celebration;

- Comparing self (as inadequate) to others, jealousy;

- Frustration;

- Guilt, feelings of failure;

- Loneliness; and

- Rebellion.

Research suggests that more extroverted personality types, status or image-conscious people, and those who prefer to live in the moment and make quick decisions are more likely to be impulse shoppers.

Regular social media users and those who treat shopping as a hobby are more likely to have impulse shopping tendencies.

There is also evidence that people who are cautious, have self-confidence, feelings of fulfilment and a sense of being ‘in control’ of one’s life are less likely to spend impulsively.

Red flags pointing to impulse spending tendencies include:

-

- Regularly buying without planning to;

- A chronic inability to save money;

- Trouble with regular financial responsibilities;

- Tendency to use money to change feelings;

- Guilt and regret over shopping decisions;

- Owning items that barely get used; and

- Regularly return items due to a change of heart.

How to manage impulse spending

The key mindsets to develop – and hold on to – are based on awareness and planning.

To begin with, we need to be in reality. So, you do need to get real.

A great place to start is to review your last three month’s spending, comparing how much of it was planned and how much was impulse spending.

It’s essential to acknowledge which habits are helpful and which are not.

Creating a budget and knowing what you spend should be your first priority.

Knowing where your money is going will help you to determine where you need to cut back.

Budgeting is not a ‘set and forget’ task. A budget needs to be reviewed and revised. Maintaining your budget is an essential skill to learn.

You need to directly deal with temptation too. We’d suggest unsubscribing from store email lists that tend to flood you with ‘on sale now’ messages and try to make you feel like you’ll miss out on something important.

If an item on sale was something you truly needed, you would already be aware of it.

Clearing your computer cookies is a good move too. Otherwise, they will any online retailers you have browsed will constantly remind you.

It’s also important not to attempt to deny yourself any spending totally. It won’t work.

Build some splurge/ fun money into your budget that allows for occasional spontaneous spending.

Providing a limit for this type of spending allows you to give in to an impulse buy every now and then without feeling guilty or worrying about overspending.

The amount of money you set aside should be determined only after you’ve taken all the essentials like rent, groceries and bills into account and will depend on what your budget can reasonably afford.

But it’s essential to track all spending to ensure you can see patterns in your spending that might need to be reined in or reversed.

Weekly check-ins to stay accountable will help support this.

How to deal with the ‘need’ to shop

Whenever you feel the urge to buy something new, or spend money, replace the urge with something that brings you joy.

Making a list of healthy activities and rewards that you enjoy or feel satisfying.

Things like seeing a loved one, cooking your favourite meal, walking by the ocean or in the bush, gardening, or phoning a great friend you haven’t seen for ages are almost certainly more rewarding than impulsively spending.

If your impulse spending is driven by comparing what you have (or don’t have) to others, take a step back and be thankful.

Learn to be grateful for what you do have and see from this more abundant perspective.

There is plenty of practical suggestions out there on gratitude – but in essence, it’s about feeling thankful for simple things in your life, which in turn creates feelings of wellbeing and contentment.

Try to adjust your behaviour with money towards medium-term and long-term thinking.

Rather than just saying: “I can’t buy that because I’m saving money.” Think in terms of the opportunity cost, i.e. “If I spend $100 on this, I can’t put that money towards the trip next year”.

This reframing makes it a choice rather than a feeling of missing out.

Create reminders for yourself to act as reinforcement of your goals and encouragement towards saving. For example, if you’re saving for a holiday, save images of your dream destination in places you’ll see them: your screensaver on the phone, or computer, and rename your password for internet banking to your savings goal.

Some other strategies to reduce impulsive spending

Try avoiding the use of credit – it’s not easy, but it’s a great aim.

Credit cards aren’t inherently bad, but if you’re prone to impulse shopping, they may worsen your situation.

Getting rid of your credit card is equivalent to getting rid of the thing that enables you.

Learn to spend within your means and only use money you have, i.e. use your debit card or cash for purchases instead.

Buy now, pay later is essentially another form of credit. BNPL platforms allow you to enjoy your purchase straight away but defer the payments down the track.

There’s a reason some experts dub them ‘buy now, pain later’.

One way to begin radically changing our money behaviour is to experiment with a ‘no spend challenge’.

A no-spend challenge is a personal spending challenge where you cannot spend any money on non-essential items.

They can be a good strategy to implement to break spending habits. You can choose a category such as eating out, clothes or going out, or you can make it for all non-essential spending. You set the time frame and challenge.

Accountability is always a useful tool when changing behaviour – especially reducing potentially harmful behaviours.

The people you live with or spend the most time with can be a support for you. Be open and share with them that you’re trying to spend less and ask them to support you if they see you making an unnecessary purchase.

See of you can think of someone non-judgemental in your life that you trust who might be an ‘accountability buddy’ for you around your spending.

Do you have a sibling or friend who’s willing to get in your face and tell you not to buy something? Bring them on your shopping trip. Tell them what you plan to buy and ask them to talk some sense into you if you start straying from the strategy.

Practice financial mindfulness

When you are feeling a strong pull to spend money, try to take a mindful pause by asking yourself these questions:

-

- Why am I here? (In this store/ or at my computer, online shopping)

- How do I feel?

- Do I need this?

- What if I wait?

- Can I afford it?

- Where will I put it?

- Do I really need it, or is it a want?

If you find your impulsive shopping behaviour returns or is uncontrollable despite your best intentions and attempted actions, you may be dealing with a genuine shopping addiction.

Sometimes this is known as ‘oniomania’. Yes, there’s a word for it – that means it’s real.

That might take some more help, but it’s not impossible to get under control. A good place to start is a therapist trained in treating addictive behaviours.