How mindfulness helped a bunch of chronically anxious worriers.

Time magazine recently ran an article with the headline ‘how mindfulness helps you handle stress better’. So what you ask? Sounds like every second story spruiking mindfulness as a wonder cure these days, right?

Except that the article is about research done by someone who wanted to cut the crap and find out if mindfulness really does work. Or not.

At a personal level this article is it spoke to me – the writer of the story you are reading – deeply because it looked at the effects of mindfulness on a mental health problem I have suffered all my life, which at times overwhelmed me.

First, to Dr. Elizabeth Hoge, associate professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University Medical Center. “There’s been some real skepticism in the medical community about meditation and mindfulness meditation,” she said.

According to Time, Hoges he and her team wanted to deduce if people just felt better after meditating, or if doing meditating caused measurable changes in the body’s markers of stress.

So they ran people through a stress test that would give anyone rubber legs: “eight minutes of public speaking, followed by a round of videotaped mental math in front of an audience of people in white lab coats with clipboards.”

Then they made them do the stress test again, just to be sure. But first they split the group into two.

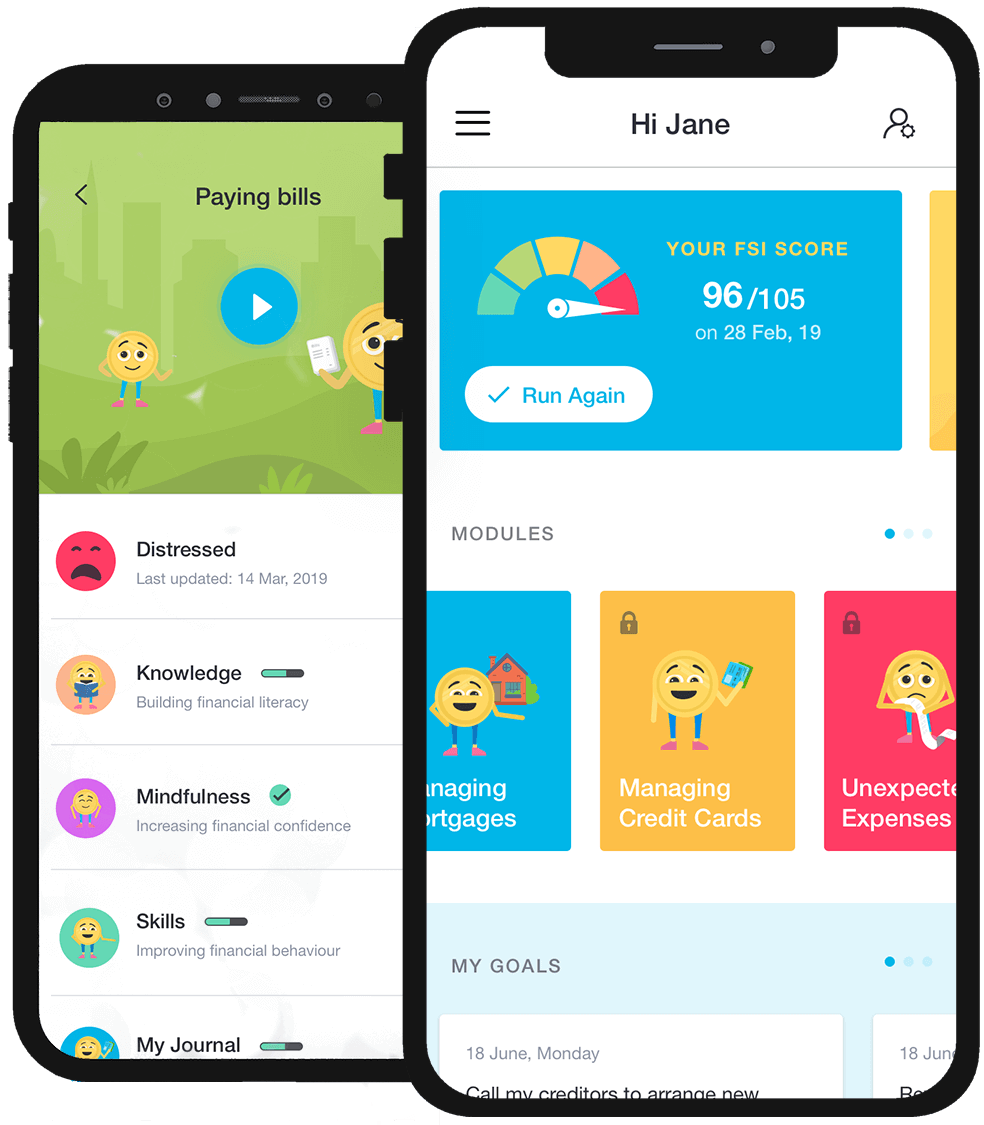

Half underwent mindfulness training (including breath awareness, body scan meditations and gentle yoga) and the other half did a stress management education course (including lectures on diet, exercise, sleep and time management).

Both groups did eight weeks training with the same amount of class time and homework.

The group that did the mindfulness training reported feeling less stressed, but blood tests showed they had lower levels of stress hormone ACTH.

The meditation group also may have been strengthening their immune systems via lower “pro-inflammatory cytokines”, alien-sounding molecules linked to depression and other neurological conditions.

On the second run of the stress test the meditation group outperformed the stress-management group by even greater margins.

“We have objective measures in the blood that they did better in a provoked situation,” says Hoge. “It really is strong evidence that mindfulness meditation not only makes them feel better, but helps them be more resilient to stress.”

Now back to me – the writer of this article – if you don’t mind.

After the death of my mother and redundancy from a 20 year career as a journalist I spent time receiving treatment for depression. To my confusion I left with a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder.

I felt dismayed and worried. How I felt was: ‘what on earth am I supposed to do with this?’

Generalised anxiety disorder, according to Way Ahead – Mental Health Association NSW, is “intense anxiety and worry about a variety of events and issues (for example, work, health, family), and the worry is out of proportion to the situation… [sufferers get] restless, easily tired, difficulty concentrating, easily annoyed, muscle tension, and/or difficulty sleeping.

While many people worry about things from time to time, people with Generalised Anxiety Disorder experience worry a large proportion of the time and it interrupts their lives. ”

Tick, tick, tick. It’s hard to admit, but this is me.

My beautiful late mother, Rosemary, may she rest in peace, worried incessantly. She worried so much it annoyed everyone around her – and mortified her teenage sons.

She worried every day until she knew she was going to die (from brain cancer) and then, quietly, she stopped worrying.

She also had trouble with anger, supressing it until she would rage. It’s even harder to admit, but this is also me. Taxi drivers who take me ‘the long way home’ have copped some fearful sprays from me over the years.

So I guess I ended up a bit like my mother, but I’d rather avoid the sad cure she found.

In the treatment centre I attended, South Pacific Private, I did a simple mindfulness meditation exercise most days – 10 minutes sitting still and concentrating on my breathing. I have done it around 70 times since leaving the centre in January, increasing the duration to 15 minutes a day. I also try to do micro sessions several times a day.

I haven’t had a blood test to show, so I don’t know how my stress hormones are or what my cytokines are up to, but I feel better. How? I worry less.

I still worry, but you have no idea how good the feeling behind that simple statement feels: I worry less.

There’s a lot more too. I am growing the ability to see my thoughts and feelings as separate from me – almost as passing storms across a blue sky – instead of experiencing them as a sort of nasty conjoined twin hissing at me.

I don’t see my thoughts as instructions, but just as thoughts.

I don’t have to let them define what I do next. If my thoughts tell me: ‘I feel down, I wonder if there’s any cheesecake left’, I can phone someone, listen to music or go for a bike ride instead. If my head sees someone smoking and wants one too, I can stop and say ‘no, that thought is not helpful’, and I do. I quit smoking in December and haven’t had a cigarette since.

I sleep better and have little muscle tension. Though am still restless, I have a level of awareness of this – and, interestingly, of how my behaviour affects others – way beyond anything I’ve ever experienced.

I still get easily annoyed – although much less so. I am more patient. If I need to stay on hold for 45 minutes to the phone company I am more inclined to express healthy anger when I get through, then detach without flogging the poor person who answers the phone.

If I do get too angry, I can cool off much quicker and apologise expecting nothing in return.

I now get on with cab drivers, even if doing so costs me $5 more.

I’m sure if I was assessed again for generalised anxiety disorder I would still fit the bill. So I am not cured. But life for me, and those very close to me, is a lot easier.

Mindfulness meditation is not a cure and there have been questions about its real effectiveness. But I know it works, and I don’t need to ask my cytokines to prove it.