Six great New Year’s Resolutions to improve your finances in 2021.

These days we know there is a correlation between our financial wellbeing and our general wellbeing. We know that toxic levels of financial stress impacts us in many different ways, it affects our relationships, our self-esteem, our social life, our productivity at work, even our physical health.

That’s why it’s appropriate to set New Year’s Resolutions for our finances — and also our related behaviours.

There’s every chance 2021 will be another tough year with COVID still a major problem, with businesses under pressure, unemployment a big worry and a wide range of ongoing social impacts.

Uncertainty and fear only add to the unavoidable problems presented by the pandemic: we still need to have positive goals and intentions for 2021, then deal with what happens as it happens.

Here are some suggestions to help you kick off 2021 in a positive way.

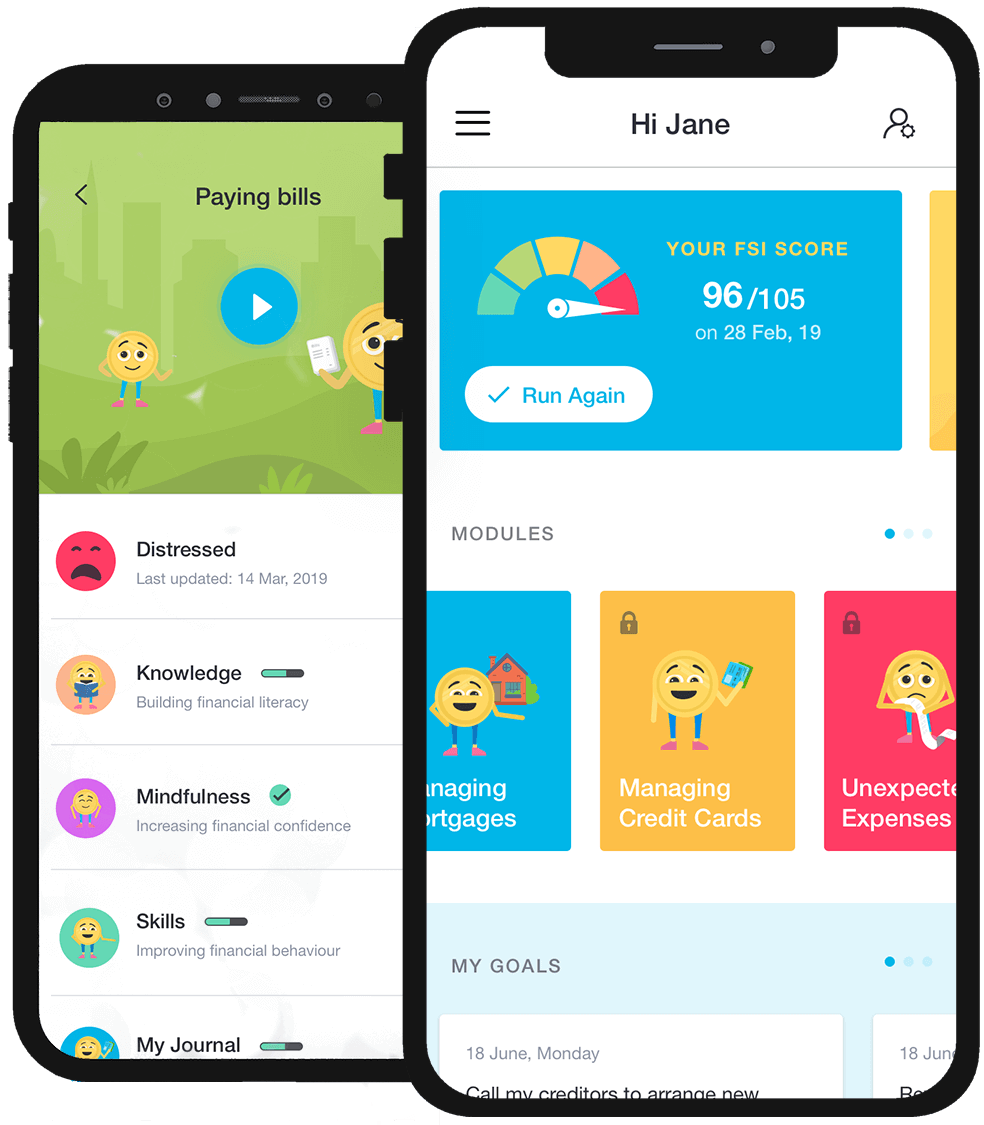

BECOME SELF-AWARE OF YOUR FINANCIAL POSITION

A great way to break through the murkiness of money problems is to answer some simple no-nonsense questions. Even if it’s a little scary, you should be clearer afterwards and probably more motivated too.

- Are your savings going up or down? What direction are your finances are headed in?

- Have you had trouble paying basic bills and/or making normal repayments?

- What are your financial goals?

- Do you fully understand your finances?

- Are you ok with being in the same position financially a year from now? Five years from now?

- Do you ever feel distracted because of your finances, including during work hours?

- How often do you spend money on things you don’t need and/or aren’t healthy for you? When did I last do this? How many times in the past month has this happened?

- Are you financially healthy but feel stressed and/or down about it anyway? Why is that?

- Do you ever experience conflict or feel anger because of your finances?

- What steps are you taking to address your financial issues? If none, what is holding you back?

Spend at least 30 minutes on this and try to share the answers with someone you trust, and also put your answers into a journal so you can refer to them later.

TRACK YOUR SPENDING

“Spend less, save more” is on just about everyone’s list of New Year’s Resolutions, ever year. It’s a great goal, but a more specific objective that will help you work towards that goal is to carefully track all your spending – on a daily basis. Use an app, or write it down on paper – whichever suits you best.

Do it for a week, then a month. Clear patterns will emerge which will help you to keep a realistic budget. Keep doing it – this is one of the best habits anyone who feels financial stress can build.

REDUCE THE NOISE

There are just too many distractions in the world today. To have any hope of living more mindfully, and sustaining financial resilience and overall wellbeing, we need to reduce the white noise in life. Here are some suggestions:

- Reduce your social media use. Cut back and make the time you spend on social media more meaningful. For example, congratulate friends on life events and achievements instead of getting dragged into debates.Post pictures and stories of something you are proud of. If you really struggle with social media, turn off notifications and set digital wellbeing timers.

- Be wary of online news. There’s an old saying that still holds true in the news business: if it bleeds, it leads. News organisations have a vested interest in bad news and scandals and that cannot be good for anyone’s state of mind.Be aware of that before you click: news sites count on a natural human curiosity to witness dramatic events.

- Plan your distractions. It’s ok to switch off and escape mentally for a while, in fact it’s essential with the pressures in life. Plan ahead for how to ‘escape’ and make an agreement with yourself to eliminate or minimise unhealthy behaviours and stick to your limits.For example, watching a movie or two episodes of your favourite Netflix show is very different from bingeing until 2am. Try one glass of wine on a Friday instead of two each night. Listen to a podcast on a walk instead of snacking.

- Monitor and reduce screen use. Are you seeing far more human faces on screens than in person? Does your screen use feel compulsive? Do you wish you could turn something off but can’t seem to?Do you have blurred vision, neck pain, headaches, irritability and trouble sleeping? These are all signs of excessive screen time.

- Don’t reply to everyone. It was true of email 10 years ago and it’s true of all forms of digital communication today. We are not saying ignore people in need, but answer what you have to. You can’t always please everyone.

- Aim for 5 minutes of complete silence each day. No screens, no music, no audio at all, no talking. Yes, it’s an old-fashioned idea but just try: it’s powerful. In that 5 minutes notice how your body feels.

UNDERSTAND WHAT YOU CANNOT CHANGE

Resisting or trying to control things that are not in our direct control is the cause of a lot of human misery. What does this have to do with financial resilience? A lot of people spend money to change the way they – or someone else – feels.

Understanding what you can’t change takes practice. Give this a try: can you actually change the fact that COVID is still in play and affecting your suburb and your company? Of course not.

Here are some other things you also cannot directly change:

- Other people’s opinions and decisions;

- Other people’s behaviours, including their flaws, habits and problems;

- Final decisions and rulings made by companies, and governments;

- The job market;

- The housing or rental market;

- The cost of buying anything;

- Money that has already been spent; and

- Debts that have been fairly accrued.

What do you think you have been trying to change that is actually beyond your direct control?

Here’s a list of things that we can change (even if it is difficult to do so):

- Our own decisions and opinions;

- Our own behaviours and how we react (including good and bad habits);

- How we spend our time;

- Our loneliness, including any tendency to repeat our mistakes (we can ask for help);

- What we spend our money on;

- Our level of savings and the direction of our finances;

- Our financial literacy;

- Debts that have been unfairly/illegally accrued

TAKE HAVING FUN MORE SERIOUSLY

True, it seems counter-intuitive to be “serious” about fun. What we really mean is to make having fun a priority. There is some science that shows how important fun is:

- It improves relationships;

- It relaxes and makes us more confident;

- It is good for our health – reducing potentially harmful hormones like cortisol and noradrenalin and improving our immune system response;

- Fun invariably leads to laughter, which also has a host of positive physiological affects including raising mood;

- It improves satisfaction levels at home and in the workplace.

So how do we have more fun? Try thinking of fun as “play”.

Play isn’t just important for children, though it’s often best with children. Play with your kids, get down on the ground with them – inside or outside. In their fort, in the dirt. It’s good for everyone involved.

If you don’t have kids, play with your dog. If you don’t have a dog, sing bad 80s music at the top of your lungs, jump in the ocean regularly, rediscover things you loved doing as a teenager. Push yourself out of your comfort zone a little, perhaps with dancing, or taking up a craft or hobby that sounds enjoyable to you.

Gentle exercise, especially when shared with others, is often good fun. It doesn’t have to be competitive – that’s a personal decision: some people find competition fun, some don’t. Go with your gut.

Whatever you do for fun, make it regular – at least once a week.

MAKE SELF-CARE A DAILY HABIT

Self-care is being written about here, there and everywhere for a reason: it’s not just a cliché or a passing fad. It’s a very broad term to cover the actions that keep your mind and body healthy. Here are 12 suggestions for valuable self-care that anyone can do:

- Face up to basic responsibilities, like booking doctors and dentist appointments;

- Keep your receipts for tax time. Your self-esteem will grow, and you will feel more in control;

- Exercise at least 3 times a week, even if you can’t face high-intensity activity. Just go for long walks;

- Don’t eat mindlessly, think about your food. Avoid huge servings, especially late at night. Eat more vegetables than processed foods. Sugary snacks and drinks are not your friends! They are bad for your teeth and lead to weight gain;

- Go to bed on time and at the same time each night. 7-8 hours’ sleep is about right, less or more might affect your health;

- Do a quick mindfulness exercise each day. Guided meditations are easiest and often free on YouTube or apps;

- Get out of your own head by helping others;

- Always have something to look forward to a holiday, a dinner, a movie, a concert, especially something that ‘makes the heart sing’;

- Find a community you identify with – separate from work and family connect with them at least once a week;

- Reach out to trusted friends when you feel lonely. It’s never a burden to hear from a friend expressing their vulnerability, it actually builds trust;

- Set aside an hour each week for honest self-reflection: look at your progress with your finances and on your goals, assess your self-care and bad habits, estimate your screen time. Are you having enough fun? Or too much? Are you wrestling with things you can’t change? Record these facts, thoughts and feelings in the same place each week.

- Don’t forget to be positive, grateful and kind to yourself!

SET GOALS FOR 2021

Just setting a few modest goals can have positive impacts on our mental wellbeing, as well as the more obvious benefits that come from even partially achieving them.

It’s important to not overwhelm your list with a ‘to-do’ list aimed at transforming every area of your life. That is a recipe for beating yourself up. But you should put some thought and some detail into the few that you do come up with.

The SMART acronym – Specific, Measurable, Achievable (or Action-oriented), Realistic (or Relevant) and Timely – is a popular, effective and useful tool for goal setting.

Here are some steps for goal setting:

- Reflect on what you have learnt from 2020;

- Reflect on what worked well for you in 2020;

- Try to remember what your goals were this time last year – are they still relevant?;

- Think about what story you’d love to tell about your life at the end of 2021;

- Brainstorm 6-10 ideas for goals, some hard, some easy;

- Trim that list back to 3-4 that feel right and/or really important (don’t pick the 3-4 most difficult!);

- Apply the SMART acronym to each; and

- For long-term goals, make sure you break them down into smaller goals, e.g. “To save $20,000 and invest” can’t be achieved quickly for someone on an average income. For most people it would only be possible with a series of smaller goals, such as:

- Calculate how much you need to save each week to reach your savings goal;

- Make a realistic budget of all your expenses;

- Work out how much income you need each week to reach the savings goal;

- Adjust the savings target if necessary;

- Evaluate your progress after 1 week, 3 and 6 weeks. Make necessary adjustments; and

- Seek help and advice on investment options.

Some general tips on goal-setting:

- Goals work best when they are clear and specific;

- Having several highly ambitious goals is probably not realistic;

- Having at least one challenging goal has positives and negatives, but produce better overall results than having only modest goals;

- Goals need to be reviewed regularly and adjusted accordingly; and

- When you evaluate your progress and find you are on track, give yourself a modest reward, but not one that undermines your efforts so far.