The real cost of gift-giving: financial stress – part 3.

In ancient history giving gifts began as part of the ritual of worship and over the centuries it has morphed into a show of appreciation. In the age of mass consumerism gift-giving has become an expensive habit too, especially in holiday season.

While most of us worry about money to some degree, gift-giving has costs we usually bear without much complaint; giving is a respected value, it feels good and it’s accepted as a cultural obligation. Besides, we have special labels for people who don’t play along with gift-giving: who wants to be labelled Scrooge or the Grinch?

Let’s take a look at one specific festive custom: the excessive expectation everyone will have a present for everyone else who arrives on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day – whether they are young nieces and nephews, twentysomethings, cousins, partners of relatives.

Even exes in attendance get a gift. It’s probably no exaggeration to say half the gifts exchanged in these situations are politely put in a cupboard when they arrive home – and forgotten. The obligation to provide a pile of gifts – of appropriate value – across extended families can add tension to what is often already awkward family gathering. It almost certainly adds to seasonal financial stress.

Never mind that in the affluent West that many of us take months to repay debts incurred at Christmas time and in Black Friday and Boxing Day sales. So, at least reasons to buy expensive gifts are out of the way after Christmas, right?

Wrong. February and March tend to have the most weddings in Australia, which means wedding costs and wedding gifts for guests. February and March also have a lot of birthday spending, as those are the second and third most common months to have a baby. From there, the retail calendar kicks in: with gift-giving the norm in Easter, then for Mother’s Day – not to mention birthdays and anniversaries for the rest of the year.

Another type of gift-giving that is anecdotally growing is also worth noting: buying ourselves gifts and treats for our birthdays or just ‘getting through hard times’ such as COVID, often just because we see appealing items in big seasonal sales.

So, how can we avoid the financial stress that comes from adding new debt to existing debt, and the symptoms and impacts of that financial stress?

Some of us at some point have completed a budget (even if we can’t always stick to it) and humble enough to get financial advice to try and do better. We are not clueless.

But without an overhaul in our thinking, choosing gifts will remain stressful for many people. There can be a huge array of options and a nagging temptation to show our appreciation – for ourselves and others – by over‐spending.

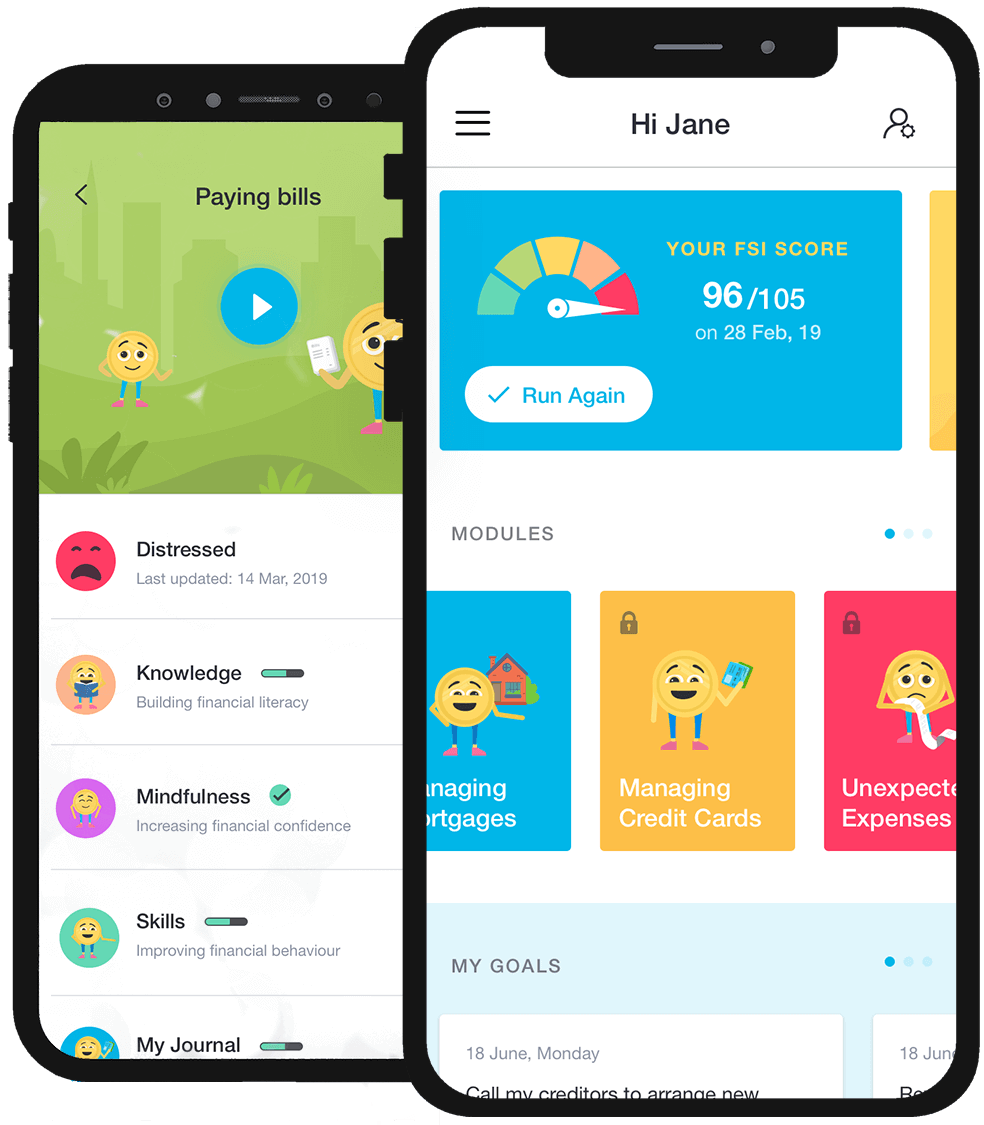

If you have tried every trick to rein in spending on gifts it could be time to try something new – using mindfulness with your finances, also known as financial mindfulness. Mindfulness is described as moment‐by‐moment awareness.

Take the example of a teenager who “needs” for a sleek iPhone 10 as a gift, if not the newest flagship Apple phone, an iPhone 12 Pro Max. An iPhone 11 Pro Max will set you back at least $750 and a Pro Max 12 starts from the mid $1500s and rapidly goes up beyond $2000.

“We all have urges that we really, really want a new gadget like an iPhone, including me,” says Financial Mindfulness CEO and Founder, Andrew Fleming.

“It feels good to take it out of the box and start using it. The feeling of having the latest technology makes you feel cool and the children love it. Like anyone else I’ve learned those feelings don’t last long and they certainly don’t improve your life, despite what the ads tell us.

“Always having the latest iPhone won’t make me or anyone else truly happy. In fact always giving in to buying the new iPhone – or the latest of any brand of device – will actually decrease happiness because it will probably contribute to increased financial stress.”

The reason those sentiments feel uncomfortable is because they’re true. Researchers from Washington University and Seoul National University, Joseph Goodman and Sarah Lim, found that giving ‘experiences’ increases the happiness of recipients more than material gifts – even if people are not socially close.

Hence the boom for online companies selling “experiential” gifts: in Australia, RedBalloon; in the UK, Red Letter Days and in the United States, retailers like Cloud 9 Living and Great American Days.

But focusing on experiential as opposed to material gifts is unarguably only half of the answer.

While the research shows a hot‐air balloon ride or chocolate‐making course should satisfy the recipient more than boxed gift wrapped with a bow, if you try to please someone with the dollar value of your gift your debt problems could get worse and that is undeniably a problem.

Ever looked at the cost of sky‐diving, rodeo‐riding or maybe cage diving with sharks? You will spend hundreds, if not over a thousand dollars on these.

Financial stress is irrefutably linked to health problems like depression, anxiety and sleep disorders so it’s not a big leap to see that the expensive gifts you buy – whether material or experiential ‐ could paradoxically lead you to feel less likely to connect with other people.

Most of us know overspending will put pressure on us, but since when did knowing right from wrong stop human beings from making mistakes?

A parent, relative or partner with poor self‐control around money will often buckle to badgering from a child, or give into a yearning to people‐please, and buy that new smartphone, tablet, a holiday or even a car.

A daily mindfulness practice will lead to a more mindful approach to gift‐giving, so we do not drift into autopilot when buying. It’s inevitable this will lead us to confront some fundamental uncomfortable truths about money. “Mindfulness helps to calm the mind and with a calm mind we make better decisions,” Fleming says.

“Sometimes it’s a better decision to treat ourselves to a book or a movie or a massage instead of the latest smartphone.”

It’s important to note mindfulness is no silver bullet – it can however help you begin to change in that area. From there we can make some deep, meaningful changes: when we are forced to face old assumptions about money.

“There’s a big mindset change some of us need to make at times like Christmas, birthdays and weddings: how much we spend on people is not automatically a sign of our value and love for each other.”

Which brings us back to gifts. You can create lasting memories with creativity and your knowledge of a person.

How about home‐made cookies baked with personal messages – each describing why you love the recipient ‐ hidden in the dough? Or a hand‐made recipe book containing meal suggestions from the recipient’s family members?

Maybe get a t‐shirt printed with the recipient’s favourite funny saying or if you have time, plan a surprise outing and put thought into favourite stops and a destination, or even fill a tall jar with inspirational quotes written and printed in different colours.

If you have lots of time, learn the guitar then write someone a song and play it for them. If you don’t have much time, spend a couple of hours hand‐writing a letter telling the recipient what they mean to you. Could any gift feel better and teach about the real meaning of value?

Time is a key resource when it comes to gift-giving; you need to know someone or learn about them to know what might make them happy. And time is valuable. Benjamin Franklin was widely credited with the unforgettable line “time is money” in 1748 (although it’s been shown to have much earlier origins, perhaps even ancient Greece).

We can spend money and time, but where spending too much money might cause you crippling financial stress, spending a lot of time only enhances relationships – especially on children – by creating last memories.

Andrew Fleming says getting our minds to a state where we can see that spending time is just as valuable as money when it comes to gifts isn’t easy. “Everyone thinks they are time-poor.

One tool I know that can really transform how much time I think I have is mindfulness. Using mindfulness when I’m spending money means I make better decisions – no doubt about it.”