Don’t blow your savings.

The endless restrictions and lockdowns Australians experienced during the pandemic did more to us than make us want to socialise and dine out.

In many people, they create a pent-up sense of not being able – or allowed – to spend money on the things we want and love.

Compounded by the increased savings stored up by months of lockdowns, many commentators and financial experts are now expecting consumers to go on a sustained spending binge.

Online sales over the coming months – from Black Friday and Cyber Monday through Christmas past Boxing Day and right up to New year sales – are expected to hit record levels.

On top of that, hotels and restaurants have re-opened and the borders are re-opening. Airlines and tourist operators are tooling up to increase capacity – and that means a flood of overseas and inter-state travel marketing is about to hit the public.

Millions of Australians’ credit cards and buy now, pay later accounts look set to blow out.

But the resulting temptations – and pressure – to spend up holds a serious threat to something incredibly important to anyone wanting to improve their financial wellbeing and reduce their financial stress.

That precious asset is our savings.

Why shouldn’t I spend my savings?

Of course, you can spend your savings – especially if it’s yours alone.

But should you?

There are powerful reasons it’s very unwise to spend your savings.

Draining savings is a sure way to begin an unhealthy habit of living beyond your means – exactly the opposite behaviour that allowed us to grow savings in the first place.

Saving from a low base is hard, it’s like struggling up a tall ladder.

Living beyond our means has an inevitable outcome too: without the capacity to continually increase your income, it will lead to acute and probably chronic financial stress.

In other words, living beyond our means is trying to live in a fantasy.

Splurging from our savings is akin to tumbling down that ladder.

If it’s joint savings we are talking about, then spending from that without the consent of your partner is a breach of a relationship boundary.

What if you both agree to splurge your joint savings? See the opening point above – you can, but it’s unwise.

Why do I need to safeguard my savings?

A big reason spending your savings is a negative is you will fall further and further behind in wealth creation goals.

‘Hanging onto savings is an opportunity to get ahead financially which generally is what the wealthy are doing,’ says Hamish Ferguson, of Vision Property and Finance.

“They are purchasing assets and not spending as much proportionally on consumption,” he says.

Paying attention to successful wealth creation strategies is crucial for people who wish to do more than survive.

To put it crudely, how we save and what we do with those savings may determine which one of these two categories we fall into: the ‘haves’ or the ‘have nots’.

“If our desire is to be in the earlier category then we need to limit our consumption and ensure that a savings/investment plan is part of our budgeting,’ Mr. Ferguson says.

“If this is not the case, then we will end up in the have nots and as suggested only have enough to survive.”

Mr. Ferguson says there are financial ‘headwinds’ coming so keeping a buffer now is a sensible idea.

These include the bogeyman of the economy: a rise in inflation.

“Inflation is expected to rise so the cost of living is going up, interest rates are expected to rise which as well means mortgages and probably rent will go up over the next few years,” he says.

The power of a financial ‘buffer’

The final reason to hang onto savings seems intangible – but also something most of us can relate to.

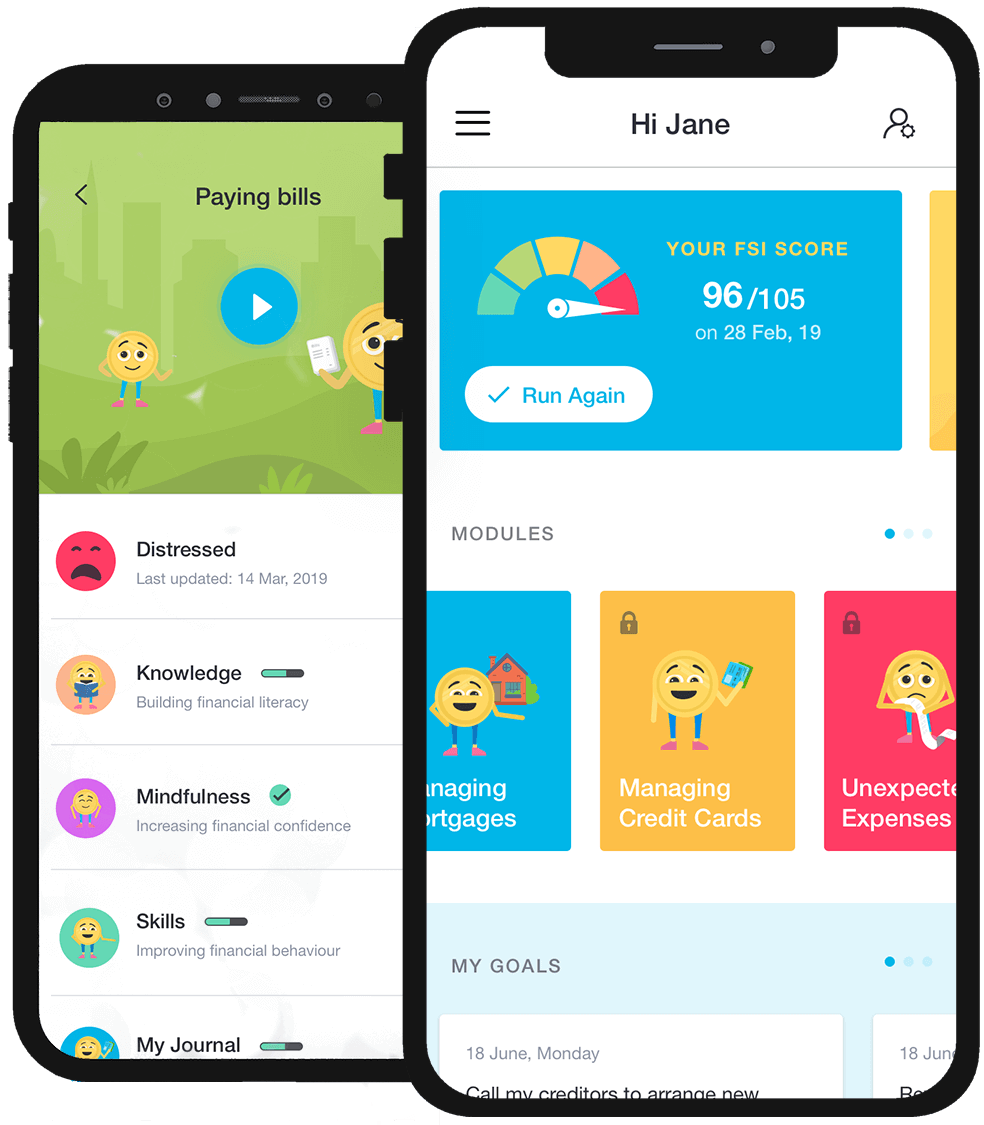

Having a financial buffer or emergency fund improves our confidence, stress levels and gives us choices in life.

“The research suggests our stress levels are lower when we have a healthy buffer,” Mr. Ferguson says.

‘This, in turn, helps us to make better future decisions and have better relationships.’

Government guidelines are that a useful financial buffer is around three months’ worth of expenses.

‘Even if you can only save a little, make a start and keep saving. The more you can regularly save, the better,’ according to moneysmart.com.au

If you put $20 a week into a savings account, you’ll have over $1,040 by the end of the year. That’s the start of a good amount of savings to give you some financial breathing space.

Choice is an important concept in all this.

“Choice is powerful, but with choice comes the discipline and responsibility to make wise decisions,’ Mr. Ferguson says.

The power to choose wisely is something that comes to us when we can practice financial mindfulness.

Is there a way I can spend or treat myself safely?

This is a great point and an important one. Life should not be relentlessly difficult and it is not meant to comprise only self-denial.

But before we prepare to treat ourselves it’s important to understand one of the universal truths of wealth creation:

“’Save then spend, don’t spend than save’,” is a great famous quote that might be helpful here, Mr. Ferguson says.

The key is having a plan to reward yourself, that is the healthy way to go.

But what does that look like?

Here’s an example. If you can set a goal and boundary to save $12,000 before rewarding yourself with a $2,000 holiday, your net benefit is $10,000.

But that benefit disappears if you ‘spend then save’.

Don’t play catch-up with money, it’s fraught with danger: it’s far better to save than spend.

Returning to the above example, once you reach $22,000 savings you can have another $2,000 holiday, or reward yourself to the tune of $2,000.

Saving before spending can be a win: win strategy.

For this strategy to work, you must – must – prioritise savings over spending, every day, every week, every month.